The CapEx Conundrum: Why Private Capital Expenditure Refuses to Rise?

- THE GEOSTRATA

- Dec 30, 2025

- 6 min read

Investment is a small but highly volatile component of a nation’s gross domestic product. As domestic belief in the future of a country’s growth feeds more into investments than corporate necessity, most fluctuations in terms of investment, particularly business fixed investment, or private capital expenditure, can be traced back to demand-side catalysts.

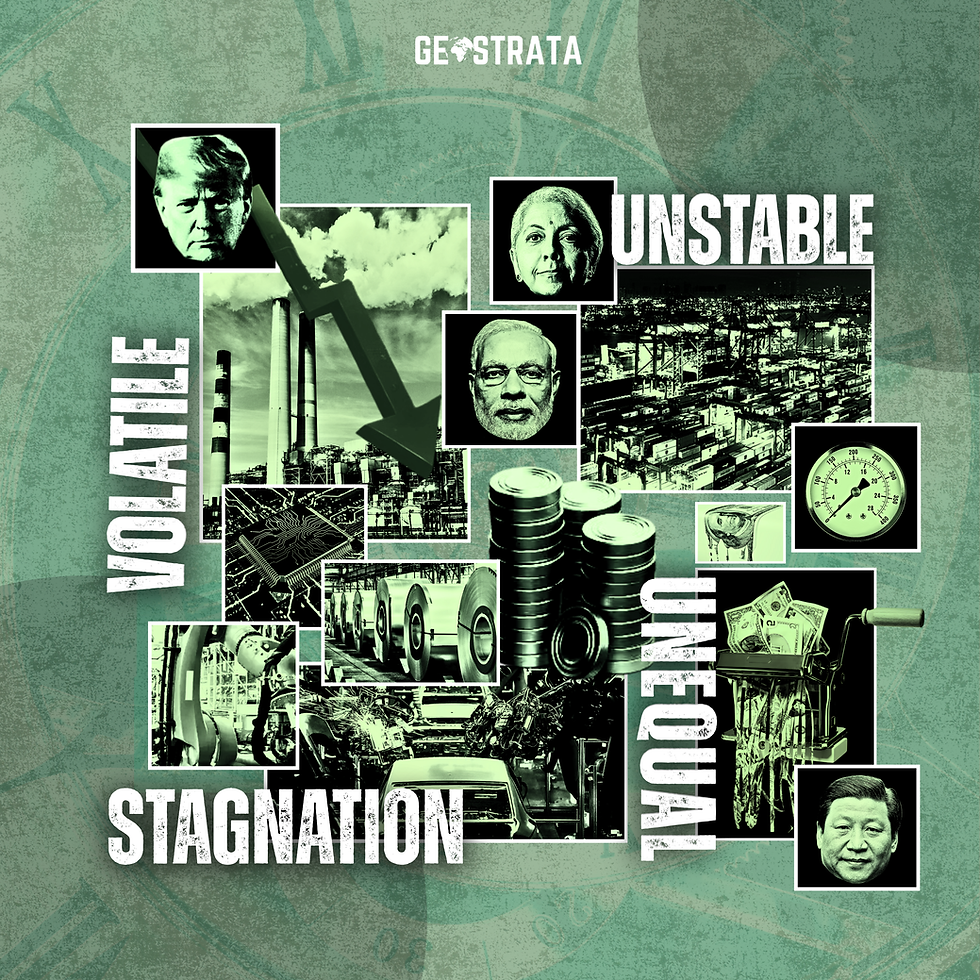

Illustration by The Geostrata

THE THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS

Investment is not merely an autonomous activity, but is undertaken by firms on account of their expectations for future demand to justify additional capacity. Macroeconomically, expected demand drives capacity utilisation, which steers profitability expectations, thereby fuelling investment decisions. When such demand becomes weak or volatile, investment naturally becomes a risky and unattractive endeavour.

In such cases, large supply-side incentives such as tax cuts, production-linked incentives, lower corporate tax rates, or eased regulations fail to translate into capital formation by virtue of the fact that firms are not convinced that consumers will buy what new capacity produces, in its simplest explanation.

Supply-side policy prescriptions cannot offset demand-side shocks, which shall be discussed at length further in the article.

DEMAND SHOCKS AND THE INDIAN ECONOMY

At the very outset of analysis, it is observable that while household consumption contributes a whopping 63.7% to India’s GDP, real wage growth for the bottom 60% has nearly stagnated over the past decade. As a result, consumption growth occurs in a K-shaped curve wherein premium and discretionary categories undergo massive booms while mass-consumption categories stagnate. Companies in the FMCG industry, automobiles, and construction signal a muted rural demand, despite being core drivers of private capital expenditure.

This directly depressed capacity utilisation, which has declined to just 65.6% after previously hovering around 70-80%, is below the threshold at which firms begin to consider new investment and not nearly enough to trigger broad-based capex cycles.

At the end of the rural and agricultural economy in India, it is not a fact in obscurity that the dynamics between employment and contribution to national income by the primary sector have been in imbalance since before one could recall, described by low productivity, terms-of-trade shocks, climate volatility, and rural indebtedness. All of which suppresses rural incomes. Given the volume that rural India contributes to mass-consumption goods, declining purchasing power constrains demand expectations.

Additionally, high financial insecurity has led households to shift from consumption to precautionary savings due to health, education, and job uncertainty, wherein a rising reliance on informal employment further weakens income stability.

Shocks on the demand side of the economy are also compounded by the persistence of vast inequalities in income as the top decile continues to account for a disproportionate share of consumption of high-value goods, while broad-based manufacturing investment is crunched by mass-market demand, as opposed to niche consumption.

The swamp of demand-side weaknesses that the lagging private capital expenditure has been founded on is not cyclical in nature, but a product of structural deficiencies, not only in the way the economy functions, but the functioning of variables that feed into it. The most pronounced of these is persistent underinvestment in the social sectors of health, education, and skill development. Productivity stagnates, leading to lower wages, lower demand, and finally, low investment, in a self-reinforcing cycle.

Similarly, the job creation remains a component of science fiction, due to which the median household income growth remains weak. Once again, consumption stagnates, causing investment to fall. The structural nature of weaknesses in domestic demand is the core reason that private capital expenditure refuses to revive itself. But how did its state deteriorate to this extent?

HOW THE WORLD VALUES INDIAN MARKETS

With the tumultuous trade dynamics that the disruption and deterioration of the credibility of Indian industries is credited to, for the sources of private capital to ignore the state and nature of geopolitical headwinds affecting, not merely business confidence and consumer sentiment, but also supply chains and overall profitability, would be fantastical.

It is undeniable that the onset of reciprocal tariffs imposed as an inaugural statement of the disruption that Trump’s return to office would define, also marked a period of ineluctable uncertainty for India’s private landscape.

Simultaneously, global capital tightened as elevated US interest rates triggered the sharpest emerging-market outflows since 2018, further constraining India’s external financing conditions. Although the country also emerged as one of the most popular “friend-shoring” locations amidst the US-China trade war, the damage was not entirely offset.

Additionally, supply-chain realignment post-Ukraine and the Red Sea disruptions raised freight costs by over 200%, thereby eroding margins and amplifying firms’ reluctance to commit to long-horizon domestic capex.

PUTTING HISTORY INTO CONTEXT

To understand the present nature of private capital expenditure, one must first turn to its historical trajectory. India has witnessed two pronounced investment upcycles in its contemporary economic history, with each one being carried by distinct macroeconomic headwinds, followed by starkly contrasting periods of deceleration.

The first wave occurred between 2003 and 2008 when a synchronised global expansion, booming exports, liquidity, and domestic confidence all converged into India’s investment supercycle. Balance sheets were strong, banks were eager to lend, and capacity utilisation levels signalled enormous room for expansion.

Private firms ventured aggressively into infrastructure, power, steel, construction, and telecom, with investment as a share of GDP rising from 13% during the economic reforms of 1991 to 21% in the early 2000s, peaking at roughly 27% in 2007-2008. The momentum, however strong, was derailed by the global financial crisis, the collapse of export markets and the eventual surfacing of systemic weaknesses in risk assessment and project selection across the thermal power and roads sectors.

The years that followed unravelled the ‘Twin Balance Sheet’ problem with overleveraged (highly indebted) corporations on one side, and banks burdened under the ever-growing weight of non-performing assets on the other. The resulting deleveraging cycle froze the pipeline of new investment and redirected corporate priorities from expansion to survival.

Even as the global economy recovered, the revival of India’s private capex remained tepid. Project cancellations in sectors like coal, mining, and telecom, spurred by judicial interventions and policy reversals, introduced a new layer of regulatory uncertainty, a terminology that acts almost as the very antithesis of bullish investment sentiment. Allocations and licenses, the most popular of which were the coal block allotments and spectrum licenses, were annulled, forcing firms to reassess the risks of long-term investments. Capital that was once optimistically mobilised, now found itself trapped.

By the mid-2010s, private investment as a share of GDP had fallen drastically. Even reforms such as the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), corporate deleveraging and the recapitalisation of the banking sector could not immediately restore investor confidence.

Quite naturally so. While balance sheets improved, demand could not be revived, and thereby, the willingness to undertake fresh capacity expansion remained as it was: negligible.

Over the decade, a form of decoupling began to emerge between corporate profitability and business fixed investment. Even as profits surged, particularly post-COVID, private firms continued to hold back on new capex, preferring to deploy surpluses towards deleveraging, dividends, and acquisitions. High profits no longer translated into high investment due to the underlying demand-side catalyst.

GOVERNMENT'S PUSH FOR INVESTMENTS

In recognition of the persistent sluggishness in private investment, the Government of India, over the years, has pursued a range of policy measures aimed at forcing a revival.

A significant pillar has been an aggressive expansion of public capital expenditure, particularly on transportation, logistics, and defence. The Union Budget has consistently raised allocations for roads, railways, and allied infrastructure in the belief that government-led investment would essentially “crowd-in” private investment by reducing logistics costs and improving market connectivity. The state has become the primary engine of fixed capital formation in attempts to offset the fact that private sector participation remains muted at best.

However, while the necessity of public capex cannot be denied, it does not automatically crowd in private capital in an environment where domestic consumption is faltering, as was the case in India. Without robust household demand, expressways and freight corridors do not translate into higher orders for manufacturers.

Another notable intervention came in 2019, when India implemented one of the most substantial corporate tax reductions globally, slashing the base rate to 22% for existing firms and 15% for new manufacturing entities. The move sought to improve competitiveness, attract foreign direct investment, and free up internal resources for domestic firms to reinvest in productive assets.

Nonetheless, firms cannot scale production up if capacity utilisation is low and real wage growth remains stagnant. Investment is ultimately anchored in the expected rate of return, not in tax concessions.

The introduction of the Production-Linked Incentive schemes composed a more targeted industrial policy offering performance-linked subsidies across sectors from electronics to pharmaceuticals and textiles. The government aimed to position India as a manufacturing alternative in global supply chains. Certain sectors, notably mobile phone assembly, saw a rapid investment inflow and output boost under the PLI.

While the intentions were pure, sectoral incentives such as PLI risk generating islands of efficiency, opposed to broad industrial rejuvenation. Investment begins to flow only into targeted sectors while the rest of the manufacturing ecosystem remains subdued, limiting the spillover effects of such incentives.

CONCLUSION

The core limitation lies in the nature of these policy prescriptions, as highlighted in former sections. These were supply-side interventions attempting to solve a demand-side problem by a fluke. The government succeeded in reducing the cost of investment, but not in enhancing the expected return, without which, private capital expenditure cannot be revived.

BY DIA ATAL

TEAM GEOSTRATA

.png)

Comments